(Quick note: my newest book, Suddenly I was a Shark! My Time with What Remains of Edith Finch is now available for purchase. Or, if you become a paid subscriber to this newsletter, you get the book for FREE, along with most of my other books and essays)

I am 40 years old, meaning I'm of the first generation to grow up with video games and the Internet. This means, of course—as the generation cycles tend to encourage—that my generation's parents feared both of these things. And so, the narrative unfolded that video games broke the children, and the Internet is where perverts thrived.

This is the advent of rock music. This is racial integration. This is marijuana. To the older generation, the change is worrisome. To the younger generation, there is no change. There is only the way it is.

Thankfully, my single mother of three kids was too busy to worry about hysteria (and so left me to play whatever video games I could), and we were too poor to afford a computer, let alone the Internet. For me, video games were never a demon. They loomed not as a specter but as a blanket.

So, as a lifelong gamer, I found myself at first confused when at the age of 11, in 1993, the US government aimed its pitchforks at video games. My world was one where video games were welcomed. This confusion quickly manifested into ardent defense because I knew (as much as a kid without hard data can “know”) that video games weren’t a universal bad. What little data has come about over the years only confirms this. To date, there’s been no reliable study to show that video games cause violent behavior (mostly because, as Alexander Kriss says in his book The Gaming Mind: A New Psychology of Videogames and the Power of Play, there have been no fair studies upon which to even build such conclusions).

But while lab-controlled experiments aren’t reliable, we do have several years of survey data that show a very positive outlook on video games. The ESA recently released its latest annual “Essentials Facts” report and, well, it’s becoming more and more obvious that video games aren’t an ever-present fulcrum of change across generations, but are, officially, the way it is.

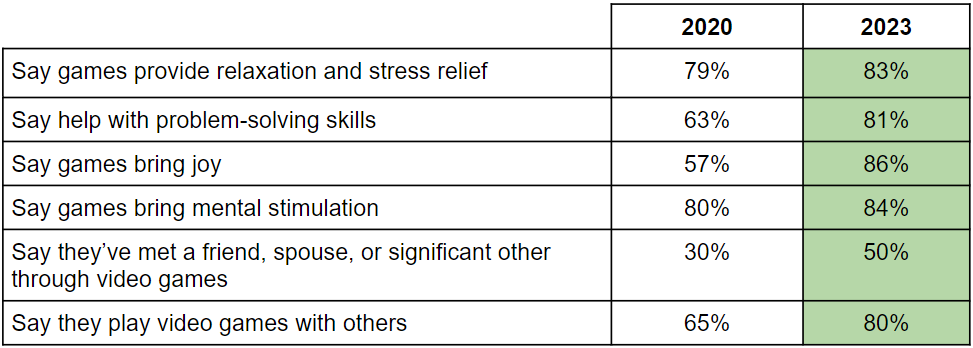

While the full report contains a lot of great information (see the entire report here), I was most interested in the results related to how players themselves perceive the benefits of games. Between 2020 and 2023, there’s a dramatic increase in the percentage of survey respondents who perceive games as offering a variety of mental and social health benefits.1

So, what does this mean? For gamers, it simply confirms what we’ve long known about video games. They can have a very positive influence on the people who play. For others, this data suggests that it’s becoming harder and harder to blame society’s ills on video games. The go-to demons for the last 40 years are now officially nothing more than strawmen.

I would also like to—but cannot ethically do so—cite the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic as a catalyst for such an increase in video game appreciation. Lockdown, in the US, largely began in early 2020. When people are forced out of the physical social circles they once depended upon, are they more open to the virtual social circles that video games provide? Possibly. The dramatic increases are telling. A 15%-point increase in the number of people who play video games with others is amazing. A 20%-point increase in people who have met a friend, spouse, or significant other through video games is incredible.

My hope is that the class of people who dismiss video games as a reactionary default faded away decades ago and that for the subsequent years, dismissal was more of a cautionary or agnostic approach, as in “video games might rot your brain, son, but you’ve never tortured a bird or lit a trashcan on fire, so go ahead with your Halos and your Grand Theft Autos.” And now, in 2023, it seems maybe that most people begin with optimism. That’s a great thing.

To be fair, 2022 showed similar numbers to 2023. I chose to use 2023 simply because it’s the most recent information available.